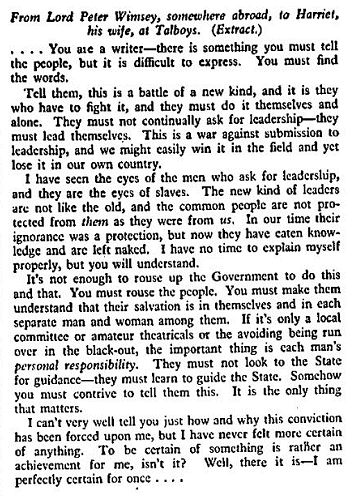

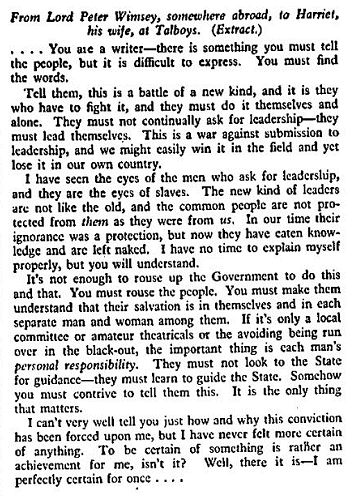

From columns Dorothy Sayers put in the mouths of her fictional detectives and their friends during World War II:

(source: The Wimsey Papers)

From columns Dorothy Sayers put in the mouths of her fictional detectives and their friends during World War II:

(source: The Wimsey Papers)

Catholic Fiction.net has just posted a review I wrote earlier, a profoundly mixed review of Shusaku Endo’s Silence. Here is the conclusion:

Given the nature of the critical literature surrounding Silence, the example of Endo’s own trajectory through Deep River, and the most obvious reading of the story itself, no one should recommend Silence as an exemplary Catholic novel without qualification. Teachers and parents who share it should be careful to surround it with good literary instruction and sound catechesis; where this is not possible, it may be better to leave Silence for later. For those who seek a novel indelibly marked by the baptismal faith of the author, and who are prepared to struggle and pray their way through a gripping and tragic confrontation between a faith shaped by martyrs and a world full of collaborators, Endo’s work has much to recommend it. Artists should seek to emulate Endo’s mastery of narrative style; and anyone interested should turn from the portrayal of Garrpe’s martyrdom to the many historical accounts of the Japanese martyrs, and pray for the souls of their kinsmen.

(source: Silence)

What are your thoughts?

Even Homer nods, and the excellent David Warren wrote a beautiful column over at The Catholic Thing which I think has some ill-considered observations.

One thing that I did not mention in my brief comment on that site is specific to the Wallace Stevens poem he discusses, there. He takes issue with the idea that the “jar” in question can reasonably be identified as a Dominion Glass Company canning jar (“The jar was round upon the ground / And tall and of a port in air. // It took dominion everywhere”). Now, if he has specific historical or biographical data that demonstrate that Stevens could not have meant a Dominion jar, or must have meant something else (and my cursory research has not turned up any), Warren does not share it. Instead, he says that this reference is “a (typically Stevensian) irony.”

One thing that I did not mention in my brief comment on that site is specific to the Wallace Stevens poem he discusses, there. He takes issue with the idea that the “jar” in question can reasonably be identified as a Dominion Glass Company canning jar (“The jar was round upon the ground / And tall and of a port in air. // It took dominion everywhere”). Now, if he has specific historical or biographical data that demonstrate that Stevens could not have meant a Dominion jar, or must have meant something else (and my cursory research has not turned up any), Warren does not share it. Instead, he says that this reference is “a (typically Stevensian) irony.”

Irony, however, is hardly meaningless decoration in a poem like this; and to say “irony” while refusing the most obvious literal significance (that a jar with a round bottom, taller than wide, open at the top, and suggesting “dominion” is likely a jar made by Dominion Glass Company, which was in mass production in 1918) is to render the poem more opaque to reality and less definite; it is to choose the writer’s preferred meaning over the poet’s work–which is just the sort of critical error that Warren sets out to criticize.

My comment:

I fear that the estimable and enjoyable David Warren has stumbled into the trap of doing what he criticizes, preferring an elusive and allusive irony to honest criticism.

Surely, there is plenty of bad criticism out there–and plenty of bad poetry, too. In an era when criticism is written to justify the critic’s paycheck to other critics, and poetry is written to justify the poet’s MFA student loans to other MFA program participants, we are desperately in need of good criticism to answer bad poetry–and good poetry to confound bad criticism.

Warren justly argues that realist metaphysics, and ready acceptance of the gifts God gives us, are necessary to good art of any kind. Huzzah! Let us close ranks.

It seems a bridge too far, though, to suggest–and possibly I am reading Warren harder than he wants me to, I confess–that “all true critics” are mimeticists, judging art by its conformity to [consensus view of] empirical reality. Surely great art also declares realities beyond nature, gracious realities which heal and perfect nature, and which also therefore confront the wounds of nature. Would you not agree? And surely competent criticism recognizes that “literary criticism should be completed by criticism from a definite ethical and theological standpoint,” as T.S. Eliot so memorably posits. Must you not agree?

It seems to me that supine “appreciation” simply lets bad poetry, and the bad philosophy that accompanies it, go unanswered. Warren objects to criticism because there is so much bad criticism, like those who object to philosophy because there is so much “philosophy and empty deceit” in the world.

The Catholic critic and the Catholic poet will have to be more than mere mimeticists, and more than mere “appreciators,” in order to co-operate with grace and confound bad critics and poets.

The results may be jarring.

When I have a class that I think can handle it appropriately, and a bit of time at the end of term when the teaching is almost all done, I like to do an exercise in honest peripatetic pedagogy. I hand out brightly colored note cards, and ask each student to quickly write down one question they’d like me to answer for the whole class–any question, no matter how irrelevant–and then to flip it over and write one statement–any statement, no matter how deep or trivial–they’d like to share with the whole class. I ask only that their question and statement seem to them to have similar “weight,” and that they be willing to have their statement read in order to get their question answered.

Sometimes it goes flat; sometimes it creates the kind of conversations we all too rarely enjoy with our students, these days.

I fielded questions about “Why don’t we read more poets who are still alive?” (too many of them, too hard to choose, free verse not the best introduction to verse, lack of public domain etexts) and “How do you make poetry matter when people are deaf to it?” (I quoted Dana Gioia on that one, of course).

Then imagine how my mind began to race when I flipped over the card that read “What is the meaning of life?” and “To give glory to Jesus.” The student, for good measure, had drawn a line from his phrase back to the question, presumably to make sure I couldn’t miss that his sentence fragment would be unintelligible except as answering his question. Continue reading

Certain teachers and homilists consistently rub me the wrong way, reading Biblical texts in ways that seem to mean less after their explications than before.

Maybe you know the kind I mean. They teach about the Resurrection, and they do so with utter conviction that Jesus Christ really did rise from the dead. But somehow it all turns out to “really be about” how believing in the Resurrection helps us to help each other and be open to new ideas.

the Gnostic Ogdoad, a manifestation of dualism–the only way from God to humans is through concepts untainted by material embodiment

And, if you’re listening often enough, you notice that the same conclusion follows from every passage. Sometimes it corrects a misapprehension: the account of the rich man and Lazarus really should be read more emphatically in terms of the identity of the rich man’s failure of charity (in ignoring Lazarus) with his failure of faith (along with his unbelieving brothers) and his lack of well-founded hope (“in hell he lifted up his eyes”). The tendency I grew up with, of looking at this account primarily as an exposition of the nature of Hell, was arguably less helpful.

Nonetheless, the parable of the Pearl of Great Price should surely not be read so that our joy in finding the Gospel is merely or most emphatically an example of our joy in finding any of the gifts God gives us, though certainly every gift of Creation is finds its ultimate goodness united to the Gospel purpose of the Creator who calls us together in one Body with His Son. Continue reading