Aristotle:

The discussion of the first question shows nothing so clearly as that laws, when good, should be supreme; and that the magistrate or magistrates should regulate those matters only on which the laws are unable to speak with precision owing to the difficulty of any general principle embracing all particulars. But what are good laws has not yet been clearly explained; the old difficulty remains. The goodness or badness, justice or injustice, of laws varies of necessity with the constitutions of states. This, however, is clear, that the laws must be adapted to the constitutions. But if so, true forms of government will of necessity have just laws, and perverted forms of government will have unjust laws.

(source: The Internet Classics Archive | Politics by Aristotle)

Livy:

Henceforward I am to treat of the affairs, civil and military, of a free people, for such the Romans were now become; of annual magistrates and the authority of the laws exalted above that of men. What greatly enhanced the public joy on having attained to this state of freedom, was, the haughty insolence of the late king: for the former kings governed in such a manner, that all of them, in succession, might deservedly be reckoned as founders of the several parts at least, of the city, which they added to it, to accommodate the great numbers of inhabitants, whom they themselves introduced. Nor can it be doubted, that the same Brutus, who justly merited so great glory, for having expelled that haughty king, would have hurt the public interest most materially, had he, through an over hasty zeal for liberty, wrested the government from any one of the former princes. For what must have been the consequence, if that rabble of shepherds and vagabonds, fugitives from their own countries, having, under the sanction of an inviolable asylum, obtained liberty, or at least impunity; and uncontrolled by dread of kingly power, had once been set in commotion by tribunitian storms, and had, in a city, where they were strangers, engaged in contests with the Patricians, before the pledges of wives and children, and an affection for the soil itself, which in length of time is acquired from habit, had united their minds in social concord? The state, as yet but a tender shoot, had, in that case, been torn to pieces by discord; whereas the tranquil moderation of the then government cherished it, and, by due nourishment, brought it forward to such a condition, that its powers being ripened, it was capable of producing the glorious fruit of liberty.

(source: The History of Rome, Vol. 1 – Online Library of Liberty)

Hannan:

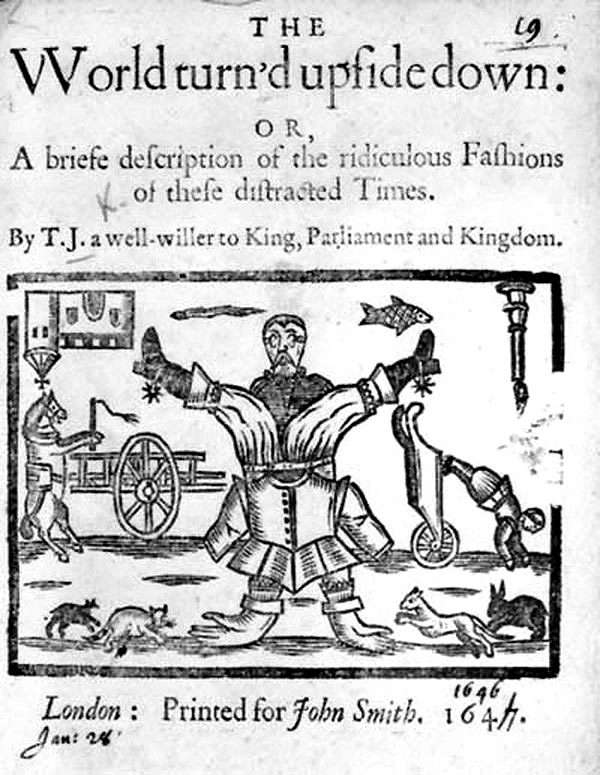

If there’s one thing that distinguishes English-speaking civilization from all the rival models, it’s this: that the individual is lifted above the collective. The citizen is exalted over the state; the state is seen as his servant, not his master. If you wanted to encapsulate Anglosphere exceptionalism in a single phrase, you could do a lot worse than what John Adams said about the Massachusetts state constitution: “A government of laws, and not of men.” Except that those words were not John Adams’s; he was quoting a seventeenth-century English Whig, James Harrington—neat proof of the shared inheritance that binds us together.

(source: How To Noisily Concede Your Liberty | Hang Together)

Before I move on, I just want to offer two bullet points in response to the assembled quotations above:

- Elision: By the time we get to the end of the citation chain (roughly, and obviously with gaps, Aristotle, Livy, Harrington, Adams, Hannan) the distinction between “the constitution” of a society–the historically contingent distribution of power (economic and coercive) and cultural authority by which “a people” subsist as such (possibly across many regimes)–and “the laws” of that society has been elided. Note that for the classical tradition, the fitness of a regime to the constitution of a society is crucial (see Cicero especially). Burke would be helpful here.

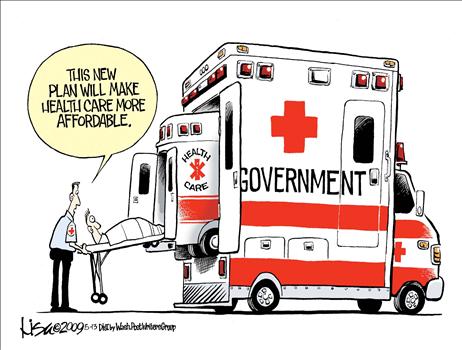

- Conflation: Hannan also conflates individualism (strictly, the doctrine of “popular sovereignty”) with republicanism (to which “of laws not men” properly belongs), and in so doing also conflates this individualistic republicanism with some species of managerialism (or administrative state). I expect a protest on this last, because it seems unlikely that Hannan has this in mind; but if each “individual…is exalted above the state” so that the regime must be seen as “his servant,” and if we don’t simply classify this as empty rhetoric, then the regime’s sole business will be to apportion services to all of its masters. Ineluctably, this will produce a society of DMV employees, educrats, special-issue “czars,” executive orders, rule interpretation memos, and other panjandrums and panaceas, not of laws. This is a common trajectory from individualism to totalitarianism, and speaking English does not immunize us against it.

Now, I understand Dan’s recent post “How To Noisily Concede Your Liberty” to say that we should argue “I should be permitted to [X]” based on the principle “because everyone should be permitted to [X]” rather than “because I have a religious obligation to [X].” I argue that we should do both, and I have both principled and pragmatic reasons for doing so–and reason to believe that the pragmatics are not shortsighted moves that “sell out” the larger principles.

I think some distinctions will help us reason through these matters. Continue reading →