A lot of the best stuff on this blog happens three comments deep. Quoth Greg:

In general, only a society committed to running on moral consensus can have a revolution in the strict sense of that word (as distinct from, say, mere rioting or revolt or secession). Other societies recognize no transcendent standard separate from the social or constitutional order as such, to which revolutionaries could appeal in opposition to that order. And a society committed to running on moral consensus will soon find, if they didn’t know it from the start, that the idea suggests at least the potential for revolution, and the constructive political uses of that potential (see Locke’s comment about “the best fence against rebellion”).

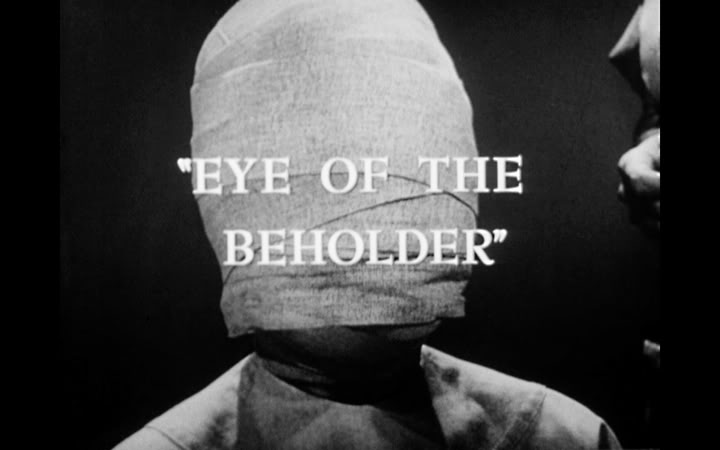

(source: Concept Art | Hang Together)

I’m too much of a Burkean not to have a large caveat on any generalization about revolution (I regard the U.S. War for Independence as an outlier precisely in its having a stronger foundation in English constitutional history than the Royalist faction in Parliament of the day could possibly have had–the “revolutionary fevers” of 1848 and 1968, Bolshevism, and even to some extent the abortive “Arab Spring,” all seem far more typical of revolutionary theory and reality, to my mind).

That to the side, it simply must be true that there can be radical improvement in a society’s power structure only when the society acknowledges some common basis for appeal beyond the regime–absolutely. It must be possible for all to recognize the difference between just and legitimate authority, however incidentally froward or unfair, and the tyrant; and to recognize who has the authority to restore justice by deposing the tyrant; and to recognize the direction for change toward a more just and legitimate authority in the aftermath. Fail any one of these, and the actions are unjust and the results detrimental to society, state, morality, and law. A chief problem of most 20th-Century democratic reasoning, in fact, is that it suppresses the possibility of one or more of these things (see under “government is the one thing we all do together” for examples).

I will point out one other thing, too: This change can only possibly be improvement when the common basis is, in fact, true–is reality itself, made intelligible and acknowledged to be so. This cannot be done when anti-realist philosophy is treated as though it were “our last, best, hope for peace.”

Greg continues with praise for “Chesterton’s Orthodoxy, a book more praised than read.” I agree, and by chance the Chesterton Club I attend monthly just did finish going through Orthodoxy (not for the first time for most of us, and not for the first time together for those who’ve been in the club longer than I). I actually find that Orthodoxy, but especially Heretics, sometimes suffers from a too-great love of antithesis and a somewhat timebound pleasure in puncturing the ironies of contemporary cant–cant contemporary to an Edwardian, that is. Our own cant sometimes has shifted enough that Chesterton’s resonant wit goes flat, like a piano with slack strings. But at moments, Chesterton is speaking directly to our day, in words that seem more relevant now than they did when he wrote them!

(And especially in the chapter I’m about to cite, Chesterton sometimes seems as though he has imbibed more Hume than is strictly hygienic, but then so did I, so there’s that.)

I’ll just pull a passage, as an example, that touches on several Hang Together themes at once (but think of this as an invitation to read promiscuously in Chesterton’s oeuvre, not a summation):

This elementary wonder, however, is not a mere fancy derived from the fairy tales; on the contrary, all the fire of the fairy tales is derived from this. Just as we all like love tales because there is an instinct of sex, we all like astonishing tales because they touch the nerve of the ancient instinct of astonishment. This is proved by the fact that when we are very young children we do not need fairy tales: we only need tales. Mere life is interesting enough. A child of seven is excited by being told that Tommy opened a door and saw a dragon. But a child of three is excited by being told that Tommy opened a door. Boys like romantic tales; but babies like realistic tales—because they find them romantic. In fact, a baby is about the only person, I should think, to whom a modern realistic novel could be read without boring him. This proves that even nursery tales only echo an almost pre-natal leap of interest and amazement. These tales say that apples were golden only to refresh the forgotten moment when we found that they were green. They make rivers run with wine only to make us remember, for one wild moment, that they run with water. I have said that this is wholly reasonable and even agnostic. And, indeed, on this point I am all for the higher agnosticism; its better name is Ignorance. We have all read in scientific books, and, indeed, in all romances, the story of the man who has forgotten his name. This man walks about the streets and can see and appreciate everything; only he cannot remember who he is. Well, every man is that man in the story. Every man has forgotten who he is. One may understand the cosmos, but never the ego; the self more distant than any star. Thou shalt love the Lord thy God; but thou shalt not know thyself. We are all under the same mental calamity; we have all forgotten our names. We have all forgotten what we really are. All that we call common sense and rationality and practicality and positivism only means that for certain dead levels of our life we forget that we have forgotten. All that we call spirit and art and ecstacy only means that for one awful instant we remember that we forget.

(source: Orthodoxy – Christian Classics Ethereal Library)

Why must we characterize all revolutions as sharing a general character and then strain to explain away the exceptions? Cannot each revolution be good or bad according to its own character?

You can, sure. I guess it comes down to what conversation you’re having. But “good” or “bad” are pretty large categories, and efforts to whittle them down to something manageable are likely to rest on resemblances and distinctions.

So I can posit “good revolutions” and “bad revolutions” and then ask “are there general characteristics of good revolutions?” to learn from, and “do most recent revolutionary movements fit these characteristics?” And from what I’ve seen, that ends up replicating in different terms the “typical modern revolution” structure, because a certain ideology of revolution has been replicating itself through most of the past three centuries.

To my mind, attempting to describe the conditions under which we get a different result seems useful, and I’m not sure how we’d accomplish that if we too radically particularize the question.

…and given that “the way of a man seems right in his own eyes,” it seems important to be as clear as possible about the relationship between the ordained norm (obedience to legitimate authority) and the extraordinary situation (legitimate overthrow of tyrants). Not least because being unclear about that makes it as hard to rally society to resist tyranny as it does to encourage respect for rule of law.

I wouldn’t overemphasize the distinction between the “norm” and “extraordinary situations.” The same moral imperative must structure both. Half our problem is that our leaders are essentially allowed to do whatever they want if they can portray it as an emergency response. Hence my reference to Locke’s principle that acknowledging the right to rebellion is “the best fence against rebellion” – that is, when the rulers know they can be cashiered if they get too far out of line, they’re less likely to get out of line. The right to rebellion is not something you need on rare occasions but something that should structure the whole social order.

“The same moral imperative must structure both” — we agree.

“our leaders are essentially allowed to do whatever they want if they can portray it as an emergency response” — yes, it’s the old problem of the Republic ending up with a Caesar.

I am tempted to gloss the question as pedagogical, or perhaps heuristic: how does one expect a society to learn the lesson that every person cannot be judge in his own case, and especially that an enthusiasm-driven mob cannot be judges in any case, while also learning to recognize and resist tyranny? Surely a people must be taught to recognize the historical “shape” and constitutional conditions for legitimate use of power, if they are to have reasonable hope of resisting tyranny and establishing justice.

On of the problems of revolutionary ideology is that it has taken words with an entirely just negative charge–“rebel” being a key example–and recast them as words which, for any idiosyncratic reason, may be employed as positive propaganda. But to “rebel” in the proper sense of taking actions in defiance of legitimate authority is not laudable–and the basic undertaking of apologists for any legitimate “revolution” must be to establish that this is not “rebellion” at all, but lawful resistance to unlawful tyranny.

For the rule of a tyrant is no law at all!

Once again you generalize about “revolutionary ideology” without basis. Is there a coherent “revolutionary ideology” about which we can thus generalize? Your overzealous induction almost makes me want to reconsider my reputation of nominalism.

Well, my basis for continuing to speak in terms of the pretty well-established history of ideas pertaining to revolution is in the paragraph before that: I think at minimum we have a pedagogical and heuristic problem to solve that is best solved by observing the differences between instances of legitimate overthrow of tyranny and rebellion against legitimate authority.

If you think there is no common cultural basis for the rhetoric that drove events in 1789, 1848, 1917, 1968, and most of “Arab Spring,” then I suppose it doesn’t make sense to suggest that 1776 was in important ways rather different from them.

I’m not sure what you gain from urging radical particularity here that doesn’t undercut your general approach elsewhere, though. I’m just using the term “revolutionary ideology” in the way that the theorists of revolution who defined and popularized the term “ideology” did, albeit I am a critic rather than an advocate of their approach.

I’m happy for anyone to make tidier distinctions when my sketches are hasty–we could throw lots of grit into the analysis by looking at less globally significant and widely theorized cases, like the Texians or various South American and African revolts, and differentiating these from coups d’etat, foreign-run insurgencies, etc.–but I can’t see the overall consistency in your approach, here. When I willingly concede the greater justification for the American War for Independence (despite its tainted popular-revolution rhetoric at Paine, e.g.), you seem to urge obliteration of that difference, so that we should regard all “revolutions” as one sort of thing. Then, in the same breath, you urge a radically particular analysis of each revolution as “good” or “bad” on its own terms (whether of nature, consequences, or both, would be worth looking at). But in this analysis of what we provisionally agree is some thing called “revolution,” of which some instances are “good” and some “bad,” you seem determined not to see any common cultural foundation for “bad” revolutions which might distinguish them from “good” ones–or at any rate, you seem determined to reject that analysis if “bad” ones turn out to be “typical” ones.

But I see no sensible reading of the history of the world since 1789 that both identifies some set of phenomena as “revolutions” and evaluates them in terms of their cultural foundations, nature, and consequences that does not generate a rough lineage of ideas, models, and “moments” pertaining to “revolution,” a notion reified by the combined force of words and weapons and thus made subject to real analysis.

The Lockean analysis that defended the Parliamentary revolt in 1688 (without relying on apologies for the Regicide), an analysis that in the hands of talented Americans doubled back with a vengeance on the Royalist faction in Parliament (i.e., the “absolute power to a king absolutely dependent on us” party, not to be confused with the Jacobites or the more radical Whigs), does share important moments with the Rousseauvian lineage of the 1789 radicals. Both valued Montesquieu at the inception of their new republics, for example. But the legacy of Locke in the Anglosphere is simply not the same as the legacy after Hegel, the Young Hegelians, and the revolt against Hegel that defined the emergence of a coherent statist philosophy in Europe, and it is against the adoption of that philosophy in the States that we ought to have been making common cause since it began to make inroads with the Progressives and became a full-fledged component of American political practice at Wilson.

I continue to prefer to distinguish some grounds for participation in the American War for Independence that would not justify participation in other revolts; and I continue to see, both in theory and in history of ideas, a distinction between the broad norm “let every soul be subject unto the higher powers” and the narrow set of circumstances in which the even broader norm “for the Lord’s sake” justifies resistance to the unlawful acts of tyrants. Precisely insofar as such a circumstance only appertains when someone has overstepped divinely ordained boundaries, such a circumstance is always extraordinary.

So what you are calling revolutionary ideology is really only French revolutionary ideology. Were there no revolutions before 1789? Were there no revolutions against the communist states in the 20th century? No Arab spring? Are the defenses of tyrannicide in Aristotle, Cicero, and Aquinas part of what you call revolutionary ideology? Or is perhaps the tiny little cherry picked selection of revolutions you’re pointing to a distinct phenomenon that needs to be dealt with on its own terms?

Invective and misrepresentation on your part aside, what is your point? Are you just venting irrational animosity toward me? I fail to see what I have done to earn your constant carping.

I have repeatedly stated that tyrannicide is defensible. So emphatically, in fact, that my great concern is not to accidentally suggest to some unbalanced soul that immediate tyrannicide is called for!

I have repeatedly stated that I think one can distinguish just resistance to tyranny from rebellion as such. I began by explicitly distinguishing such cases–as in the case of the American War for Independence–from a strain of modern thought which justifies “rebellion” as a necessary phase of human growth (see my extensive selections from Bakunin) and which calls for “revolution” as a continuing phase of political activity. That strain of modern thought is cultivated in the Rousseau-[Hegel]-Marx lineage that generates both radical and “liberal” totalitarian statism. It is the default meaning of “revolution” and “rebellion” in popular usage, and in most academic usage when not otherwise carefully defined, for at least our entire lifetimes.

If you choose to be idiosyncratic in your usage, you have no call to berate me for it. You wrong me.

And Locke would be appalled at your slipshod usage of language.

Okay, rereading what I wrote I can see that I’ve been ungracious. I apologize. Let me step back for a bit and try again when other, unrelated problems aren’t hindering my temper.

Sorry if I’ve provoked reactions–quite unintended. Anyway, online discussion always has these perils. I keep meaning to go back through more old Hang Together posts and make some notes, to clarify the lines of similarity and difference, here….