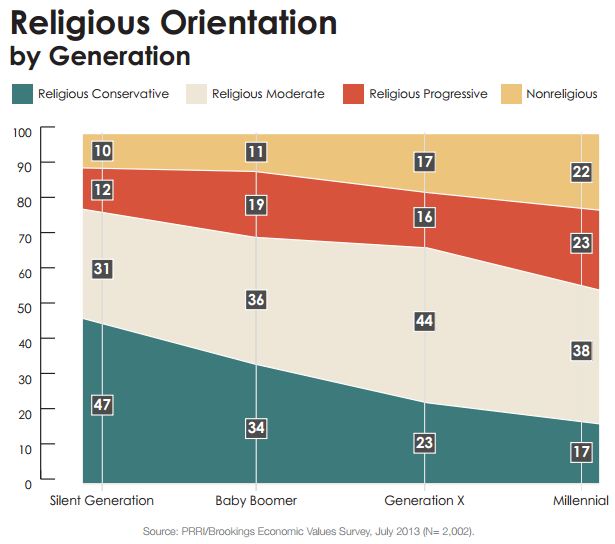

Lots of attention for Brookings’ Economic Values Survey. Left-leaning media outlets are crowing about the declining numbers of people who self-identify as religious conservatives, particularly among young people. As the above chart shows, the decline is driven not primarily by a leftward shift in American religion but by the exodus of young people from self-identified “religious conservative” populations into a “non-religious” identity. This is once again the rise of the Nones, a topic we’ve discussed before here on HT.

Which is not to say there’s been no leftward shift at all. George Weigel points out that evangelical institutions of higher learning are starting to follow both the secular and the Roman academy on their “trail of tears” toward “a sojourn into a new wilderness” of socialistic claptrap, trading their entrepreneurial birthright for a mess of redistributionist pottage.

In an excellent post, Josh Good makes the case for long-term optimism, partly because the teachings of Christianity really do align with the entrepreneurial mindset and the spirit of enterprise, rather than with the endless growth of the nanny state. I agree. Good also appeals to the greater cultural integrity of conservative denominations as against progressive ones; that’s true as far as it goes, but the question is whether those conservative denominations are going to remain “conservative.”

One strategic problem we’re going to have to wrestle with is the very language and concepts of “conservatism” and “capitalism.” The economy built on enterprise, entrepreneurship and opportunity cannot survive if it is something supported only by one side of the political spectrum. (In saying so, I’m only following the lead laid down by Charles Murray and others.) So the identification of that economics with “conservatism” is strategically problematic. Intellectually problematic, too, because the entrepreneurial economy is as much about progress (the advance of human flourishing) as it is about conservation. Hence the increasing number of self-identified “progressive” intellectuals and celebrities who embrace free enterprise, at least in principle, as the best way to accomplish their goals.

Also problematic is the word “capitalism.” Thanks to a century of woolly thinking kicked off by Max Weber’s execrable book, large numbers of people insist that the word “capitalism” simply means an economy that runs on greed. I have heard them say so myself, numerous times. And most of the time they are not open to hearing alternative perspectives; if you challenge the notion that capitalism is a system that runs on greed, you are only a huckster for the system that runs on greed (or a dupe of its hucksters). “Free markets” and “free enterprise” have the same problem, though less severely. “Freedom” still resonates to some extent, particularly with evangelicals if you can show the links between religious freedom and economic freedom – but it also raises suspicions that need to be allayed. “Entrepreneurial economy,” “spirit of enterprise” and “opportunity” seem to open doors, and I expect we’ll be using more of that language in the years ahead.