The encounter between the 21st century and American evangelicalism has reached an important turning point. The Gospel Coalition, one of the nation’s largest and most important evangelical church networks, has just unveiled its own new catechism, the New City Catechism. (Full disclosure: as readers of Hang Together already know, I publish articles on TGC fairly regularly.) The whole thing is very impressive. You download an app that not only gives you the catechism – in adult and child versions – but also explanatory videos, passages from great theologians of history, devotionals, etc. They didn’t cut corners on this.

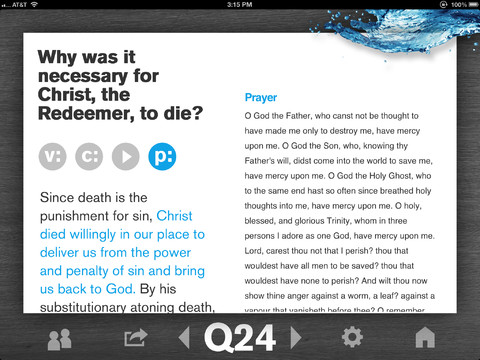

They’ve culled material from the Heidelberg, Geneva and Westminster catechisms, relying especially on the Heidelberg. You can see why; the Heidelberg is the most pastoral of the three, making it the easiest fit for the relatively emotive and narrative mental environment of early 21st century America. The NCC follows Heidelberg in opening with: “What is our only hope in life and death?” In a culture starved for hope, that’s a powerful place to begin. But more about the significance of that in a moment.

Don’t let the continuity between the NCC and earlier catechisms fool you. Publishing a new catechism is an incredibly audacious act. Although most of the words are old, TGC is making decisions on which of the old words to use from which catechisms and how to arrange and present them. That TGC can get away with publishing the NCC demonstrates the high level of theological trust its audience feels it has earned – and, as importantly, that audience’s hunger for networks like TGC to be audacious in providing a more robust set of shared resources. But more about the significance of that, too, in a moment.

As it happens, my daughter and I recently started memorizing the Catechism for Young Children together. The CYC, first published in the 19th century, is a simplified version of the Westminster Shorter Catechism. It begins with: “Who made you? God.” Good old fashioned Presbyterian analytical method! The questions do get harder; I’m dreading when we have to memorize the whole second and fourth commandments.

It’s going very well; after just a little work each day for a couple weeks, we’ve got the first 14 questions memorized. Only 136 to go! She loves it; not only is she good at memorizing, she really wants to know more about God. And this will give her a permanent foundation of understanding to build on throughout her life.

That’s why NCC is such a heartening development. The desire for better catechesis is moving from the “evangelicals can’t think, isn’t it such a scandal” stage, where we’ve been stuck for a generation, to the “hey, let’s roll up our sleeves and actually do something about this” stage.

I’ll be sticking with the CYC, mainly because it’s easier for a seven-year-old; the NCC’s child version is more suitable for 4th or 5th grade. Another reason is the value I place on maintaining historic continuity with my Presbyterian tradition; while the Reformation taught us that traditions don’t trump everything, they’re still highly valuable in that they allow for the building up of wisdom over time in community. My hope is that when she’s older my daughter will pass from the CYC to the Westminster Shorter, which is of course what the CYC is designed to facilitate.

But a third reason brings me to the reason I think the NCC marks a turning point for American evangelicalism. I want to stick with the CYC because it affirms infant baptism, and I think that’s important. Naturally, since TGC includes churches of different beliefs about this practice, the NCC is unable to address infant baptism.

This illustrates how the future of American evangelicalism is going to do two things simultaneously: reach back to the past before the schism with liberalism in the early 20th century, while also reaching forward with entrepreneurial innovation to invent new modes of godliness for the 21st.

If you’ve been following developments in American evangelicalism, you know that church networks have been the big thing for a while now. Willow Creek is probably the biggest; TGC is the biggest Reformed network; there are plenty of others. These networks convene at huge conferences; have high-traffic websites to discuss and debate; produce and share books, videos and curricular materials; and are even beginning to serve some limited accountability functions.

They are, in short, embryonic denominations. With the NCC, TGC has taken a big step toward becoming a quasi-denomination. I expect at least some other networks to follow the same path – perhaps not with new catechisms, but with continued development of quasi-denominational functions.

I view this as a positive development. There is such a thing as human nature, and therefore some human needs (including the needs of church life) are perennial. Many of these needs used to be filled by denominations. As denominations have declined, evangelicals are increasingly seeking those needs in their networks. I am far from the first to observe this!

But while denominations are coming back, the denominations of the future are not going to be the same as the ones of the past. The two major forces that first shaped the emergence of Protestant denominations were politics (in an era when states were confessional) and doctrinal development (in an era when the ability to reason seriously about things had at least some cultural value). These factors led denominations to build up institutional power and emphasize their distinctives.

Neither of these factors – thankfully in the former case, lamentably in the latter – is a major factor just at the moment. Far more important now is the great confrontation between the Christian story of the universe and the competing stories that vie with it for allegiance in ways they haven’t since the fifth century.

So I expect the new denominations to be more tribal, in both good ways and dangerous ones, than the old denominations. I say “tribal” because that’s what you call a group that is held together more by a shared story about the universe than by shared institutions or intellectual commitments. This will allow for greater flexibility than the old denominations had, particularly in developing our networks locally rather than just nationally. It will also hopefully keep us relationally stronger and more mission-focused. (It’s hard to imagine the new denominations conducting anything like a Machen trial.) And of course it will facilitate stronger gospel unity across barriers such as ecclesiological and sacramentological differences.

On the other hand, it will be a long time before the new denominations will be able to match the old ones either in learning or in institutional development. We may never get back where we were on those measures. Don’t look for a new Westminster Assembly any time soon. And all the popular connotations of the word “tribalism” ought to give us food for sober thought.

Obviously the legacies of the old denominations will continue to matter. We are never really starting from scratch; only God creates ex nihilo. NCC’s debt to the historic Reformed catechisms makes this clear. I’m not expecting to see NCC get much traction among Pentecostal churches.

But Christianity is a religion of history; it is in fact the only world religion that truly believes in history. It says God entered time-space history and even accomplished redemption by his acts within it. No doubt he is the same God yesterday, today, and tomorrow. But we are not the same, so I see no reason to expect his work in our hearts and our world will have the same emphasis.

Watching what God does in our time, as opposed to what he did for our forefathers, will be like the difference between Shakespeare’s Roman political tragedies and his Italian romantic tragedies. The same author with the same genius, but a different setting and topic, and thus a truly different experience.

Pingback: “Fewer Protestants but Better Protestants” | Hang Together